Alpha Centauri

(Nearest star from the our solar system)

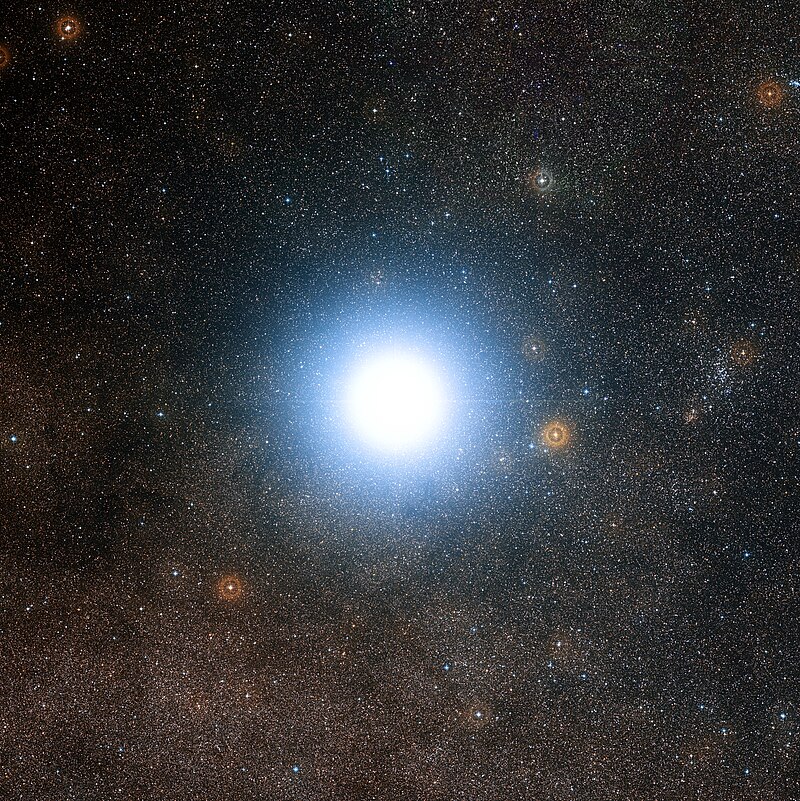

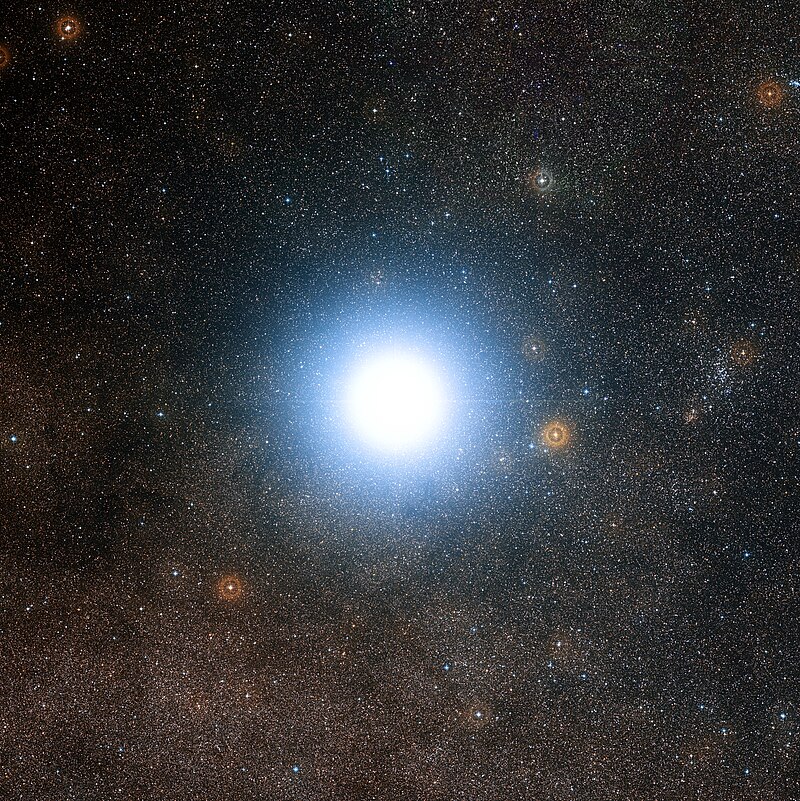

Alpha Centauri (α Centauri, abbreviated Alpha Cen, α Cen) is

the closest star system to the Solar System, being 4.37 light-years (1.34 pc)

from the Sun. It consists of three stars: Alpha Centauri A (also named Rigil

Kentaurus) and Alpha Centauri B, which form the binary star Alpha Centauri AB,

and a small and faint red dwarf, Alpha Centauri C (also named Proxima Centauri),

which is loosely gravitationally bound and orbiting the other two at a current

distance of about 13,000 astronomical units (0.21 ly). To the unaided eye, the

two main components appear as a single point of light with an apparent visual

magnitude of −0.27, forming the brightest star in the southern constellation of

Centaurus and is the third-brightest star in the night sky, outshone only by

Sirius and Canopus.

Alpha Centauri (α Centauri, abbreviated Alpha Cen, α Cen) is

the closest star system to the Solar System, being 4.37 light-years (1.34 pc)

from the Sun. It consists of three stars: Alpha Centauri A (also named Rigil

Kentaurus) and Alpha Centauri B, which form the binary star Alpha Centauri AB,

and a small and faint red dwarf, Alpha Centauri C (also named Proxima Centauri),

which is loosely gravitationally bound and orbiting the other two at a current

distance of about 13,000 astronomical units (0.21 ly). To the unaided eye, the

two main components appear as a single point of light with an apparent visual

magnitude of −0.27, forming the brightest star in the southern constellation of

Centaurus and is the third-brightest star in the night sky, outshone only by

Sirius and Canopus.

Alpha Centauri A (α Cen A) has 1.1 times the mass and 1.519

times the luminosity of the Sun, while Alpha Centauri B (α Cen B) is smaller

and cooler, at 0.907 times the Sun's mass and 0.445 times its visual

luminosity. During the pair's 79.91-year orbit about a common centre, the

distance between them varies from nearly that between Pluto and the Sun (35.6

AU) to that between Saturn and the Sun (11.2 AU).

Proxima Centauri (α Cen C) is at the slightly smaller

distance of 4.24 light-years (1.30 pc) from the Sun, making it the closest star

to the Sun, even though it is not visible to the naked eye. The separation of

Proxima from Alpha Centauri AB is about 13,000 astronomical units (0.21 ly),

equivalent to about 430 times the size of Neptune's orbit. Proxima Centauri b,

an Earth-sized exoplanet in the habitable zone of Proxima Centauri, was

discovered in 2016.

Nomenclature

α Centauri (Latinised to Alpha Centauri) is the system's

Bayer designation. It bore the traditional name Rigil Kentaurus, which is a

latinisation of the Arabic name رجل

القنطورس Rijl al-Qanṭūris,

meaning "Foot of the Centaur".

Alpha Centauri C was discovered in 1915 by the Scottish

astronomer Robert Innes, Director of the Union Observatory in Johannesburg,

South Africa, who suggested that it be named Proxima Centauri (actually Proxima

Centaurus). The name is from Latin, meaning 'nearest of Centaurus'.

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a

Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) to catalog and standardize proper names for

stars. The WGSN states that in the case of multiple stars the name should be

understood to be attributed to the brightest component by visual brightness.

The WGSN approved the name Proxima Centauri for Alpha Centauri C on 21 August

2016 and the name Rigil Kentaurus for Alpha Centauri A on 6 November 2016. They

are now both so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.

Centauri is the name given to what appears as a single star

to the naked eye and the brightest star in the southern constellation of

Centaurus. At −0.27 apparent visual magnitude (calculated from A and B

magnitudes), it is fainter only than Sirius and Canopus. The next-brightest

star in the night sky is Arcturus. Alpha Centauri is a multiple-star system,

with its two main stars being Alpha Centauri A (α Cen A) and Alpha Centauri B

(α Cen B), usually defined to identify them as the different components of the

binary α Cen AB. A third companion—Proxima Centauri (or Proxima or α Cen C)—is

much further away than the distance between stars A and B, but is still

gravitationally associated with the AB system. As viewed from Earth, it is

located at an angular separation of 2.2° from the two main stars. Proxima

Centauri would appear to the naked eye as a separate star from α Cen AB if it

were bright enough to be seen without a telescope. Alpha Centauri AB and

Proxima Centauri form a visual double star. Together, the three components make

a triple star system, referred to by double-star observers as the triple star

(or multiple star), α Cen AB-C.

Together, the bright visible components of the binary star

system are called Alpha Centauri AB (α Cen AB). This "AB" designation

denotes the apparent gravitational centre of the main binary system relative to

other companion star(s) in any multiple star system. "AB-C" refers to

the orbit of Proxima around the central binary, being the distance between the

centre of gravity and the outlying companion. Some older references use the

confusing and now discontinued designation of A×B. Because the distance between

the Sun and Alpha Centauri AB does not differ significantly from either star,

gravitationally this binary system is considered as if it were one object.

Asteroseismic studies, chromospheric activity, and stellar

rotation (gyrochronology), are all consistent with the α Cen system being

similar in age to, or slightly older than, the Sun, with typical ages quoted

between 4.5 and 7 billion years (Gyr).Asteroseismic analyses that incorporate

the tight observational constraints on the stellar parameters for α Cen A

and/or B have yielded age estimates of 4.85±0.5 Gyr, 5.0±0.5 Gyr, 5.2–7.1 Gyr,

6.4 Gyr, and 6.52±0.3 Gyr. Age estimates for stars A and B based on

chromospheric activity (Calcium H & K emission) yield 4.4–6.5 Gyr, whereas

gyrochronology yields 5.0±0.3 Gyr.

Alpha Centauri A

Alpha Centauri A, also known as Rigil Kentaurus, is the

principal member, or primary, of the binary system, being slightly larger and

more luminous than the Sun. It is a solar-like main-sequence star with a

similar yellowish colour, whose stellar classification is spectral type G2 V.

From the determined mutual orbital parameters, Alpha Centauri A is about 10

percent more massive than the Sun, with a radius about 22 percent larger. The

projected rotational velocity ( v•sin i ) of this star is 2.7±0.7 km/s,

resulting in an estimated rotational period of 22 days, which gives it a

slightly faster rotational period than the Sun's 25 days. When considered among

the individual brightest stars in the sky (excluding the Sun), Alpha Centauri A

is the fourth brightest at an apparent visual magnitude of +0.01, being

fractionally fainter than Arcturus at an apparent visual magnitude of −0.04.

Alpha Centauri A, also known as Rigil Kentaurus, is the

principal member, or primary, of the binary system, being slightly larger and

more luminous than the Sun. It is a solar-like main-sequence star with a

similar yellowish colour, whose stellar classification is spectral type G2 V.

From the determined mutual orbital parameters, Alpha Centauri A is about 10

percent more massive than the Sun, with a radius about 22 percent larger. The

projected rotational velocity ( v•sin i ) of this star is 2.7±0.7 km/s,

resulting in an estimated rotational period of 22 days, which gives it a

slightly faster rotational period than the Sun's 25 days. When considered among

the individual brightest stars in the sky (excluding the Sun), Alpha Centauri A

is the fourth brightest at an apparent visual magnitude of +0.01, being

fractionally fainter than Arcturus at an apparent visual magnitude of −0.04.

Alpha Centauri B

Alpha Centauri B is the companion star, or secondary, of the

binary system, and is slightly smaller and less luminous than the Sun. It is a

main-sequence star of spectral type K1 V, making it more an orange colour than

the primary star.Alpha Centauri B is about 90 percent the mass of the Sun and

14 percent smaller in radius. The projected rotational velocity ( v•sin i ) is

1.1±0.8 km/s, resulting in an estimated rotational period of 41 days. (An

earlier, 1995 estimate gave a similar rotation period of 36.8 days.) Although

it has a lower luminosity than component A, star B emits more energy in the X-ray

band. The light curve of B varies on a short time scale and there has been at

least one observed flare. Alpha Centauri B at an apparent visual magnitude of 1.33 would be twenty-first in brightness if it could be seen independently of Alpha Centauri A.

Observation

The two stars of the

binary Alpha Centauri AB are too close together to be resolved by the naked

eye, as apparent angular separation varies over about 80 years between 2 and 22

arcsec (the naked eye has a resolution of 60 arcsec), but through much of the

orbit, both are easily resolved in binoculars or small 5 cm (2 in) telescopes.

In the southern hemisphere, Alpha Centauri forms the outer

star of The Pointersor The Southern Pointers, so called because the line

through Beta Centauri(Hadar/Agena), some 4.5° west, points directly to the

constellation Crux—the Southern Cross. The Pointers easily distinguish the true

Southern Cross from the fainter asterism known as the False Cross.

In the southern hemisphere, Alpha Centauri forms the outer

star of The Pointersor The Southern Pointers, so called because the line

through Beta Centauri(Hadar/Agena), some 4.5° west, points directly to the

constellation Crux—the Southern Cross. The Pointers easily distinguish the true

Southern Cross from the fainter asterism known as the False Cross.

The two bright stars at the lower right are Alpha (right)

and Beta Centauri (left, above antenna). A line drawn through them points to

the four bright stars of the Southern Cross, just to the right of the dome of La

Silla Observatory.

South of about 29° S latitude, Alpha Centauri is circumpolar

and never sets below the horizon. Both stars and Crux are too far south to be

visible for mid-latitude northern observers. Below about 29° N latitude to the

equator (roughly Hermosillo, Chihuahua City in Mexico, Galveston, Texas, Ocala,

Florida and Lanzarote, the Canary Islands of Spain) during the northern summer,

Alpha Centauri lies close to the southern horizon. The star culminates each

year at midnight on 24 April or 9 p.m. on 8 June.

As seen from Earth, Proxima Centauri is 2.2° southwest from

Alpha Centauri AB. This is about four times the angular diameter of the Full

Moon, and almost exactly half the distance between Alpha Centauri AB and Beta

Centauri. Proxima usually appears as a deep-red star of an apparent visual

magnitude of 11.1 in a sparsely populated star field, requiring moderately

sized telescopes to see. Listed as V645 Cen in the General Catalogue of

Variable Stars (G.C.V.S.) Version 4.2, this UV Ceti-type flare star can

unexpectedly brighten rapidly by as much as 0.6 magnitudes at visual

wavelengths, then fade after only a few minutes. Some amateur and professional

astronomers regularly monitor for outbursts using either optical or radio

telescopes. In August 2015 the largest recorded flares of the star occurred,

with the star becoming 8.3 times brighter than normal on 13 August.

Observational history

Alpha Centauri was listed in the 2nd-century star catalog of

Ptolemy. He gives the ecliptic coordinates, but texts differ as to whether the

ecliptic latitude reads 44° 10′ South or 41° 10′ South. (Presently the ecliptic

latitude is 43.5° South but it has decreased by a fraction of a degree since

Ptolemy's time due to proper motion.) In Ptolemy's time Alpha Centauri was

visible from his city of Alexandria, Egypt, at 31° N, but due to precessionits

declination is now –60° 51′ South and it can no longer be seen at that

latitude.

English explorer Robert Hues brought Alpha Centauri to the

attention of European observers in his 1592 work Tractatus de Globis, along

with Canopus and Achernar, noting "Now, therefore, there are but three

Stars of the first magnitude that I could perceive in all those parts which are

never seene here in England. The first of these is that bright Star in the

sterne of Argo which they call Canobus. The second is in the end of Eridanus.

The third [Alpha Centauri] is in the right foote of the Centaure."

The binary nature of Alpha Centauri AB was first recognized

in December 1689 by astronomer and Jesuit priest Jean Richaud. The finding was

made incidentally while observing a passing comet from his station in

Puducherry. Alpha Centauri was only the second binary star system to be

discovered, preceded by Alpha Crucis.

By 1752, French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille made

astrometric positional measurements using state-of-the-art instruments of that

time. Its large proper motion was discovered by Manuel John Johnson, observing

from Saint Helena, who informed Thomas Henderson at the Royal Observatory, Cape

of Good Hope of it. The parallax of Alpha Centauri was subsequently determined

by Henderson from many exacting positional observations of the AB system

between April 1832 and May 1833. He withheld his results, however, because he

suspected they were too large to be true, but eventually published them in 1839

after Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel released his own accurately determined parallax

for 61 Cygni in 1838. For this reason, Alpha Centauri is sometimes considered

as the second star to have its distance measured because Henderson's work was

not fully recognized at first. (The distance of Alpha is now reckoned at 4.396

ly or 41.59 trillion km.)

Later, John Herschel made the first micrometrical

observations in 1834. Since the early 20th century, measures have been made

with photographic plates.

By 1926, South African astronomer William Stephen Finsen

calculated the approximate orbit elements close to those now accepted for this

system. All future positions are now sufficiently accurate for visual observers

to determine the relative places of the stars from a binary star ephemeris.

Others, like the Belgian astronomer D. Pourbaix (2002), have regularly refined

the precision of any new published orbital elements.

Scottish astronomer Robert T. A. Innes discovered Proxima

Centauri in 1915 by blinking photographic plates taken at different times

during a dedicated proper motion survey. This showed the large proper motion

and parallax of the star was similar in both size and direction to those of

Alpha Centauri AB, suggesting immediately it was part of the system and

slightly closer to Earth than Alpha Centauri AB. Lying 4.24 ly (1.30 pc) away,

Proxima Centauri is the nearest star to the Sun. All current derived distances

for the three stars are from the parallaxesobtained from the Hipparcos star

catalogue (HIP) and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Binary system

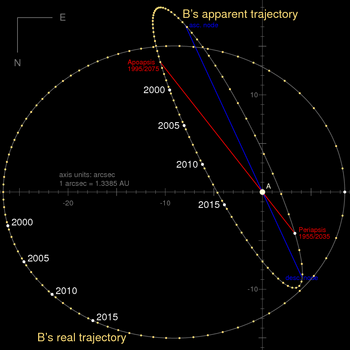

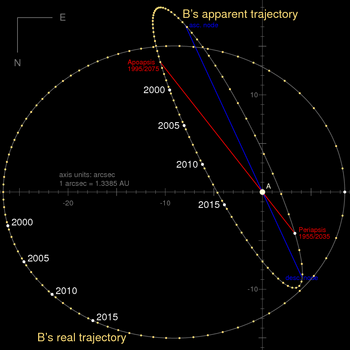

Apparent and true orbits of Alpha Centauri. The A component

is held stationary and the relative orbital motion of the B component is shown.

The apparent orbit (thin ellipse) is the shape of the orbit as seen by an

observer on Earth. The true orbit is the shape of the orbit viewed

perpendicular to the plane of the orbital motion. According to the radial

velocity vs. time the radial separation

of A and B along the line of sight had reached a maximum in 2007 with B being

behind A. The orbit is divided here into 80 points, each step refers to a

timestep of approx. 0.99888 years or 364.84 days.

Apparent and true orbits of Alpha Centauri. The A component

is held stationary and the relative orbital motion of the B component is shown.

The apparent orbit (thin ellipse) is the shape of the orbit as seen by an

observer on Earth. The true orbit is the shape of the orbit viewed

perpendicular to the plane of the orbital motion. According to the radial

velocity vs. time the radial separation

of A and B along the line of sight had reached a maximum in 2007 with B being

behind A. The orbit is divided here into 80 points, each step refers to a

timestep of approx. 0.99888 years or 364.84 days.

With the orbital period of 79.91 years, the A and B

components of this binary star can approach each other to 11.2 AU (1.68 billion

km), or about the mean distance between the Sun and Saturn; and may recede as

far as 35.6 AU (5.33 billion km), approximately the distance from the Sun to

Pluto. This is a consequence of the binary's moderate orbital eccentricity e =

0.5179. From the orbital elements, the total mass of both stars is about 2.0 M☉—or twice that of the Sun. The average individual stellar masses are

1.09 M☉ and 0.90 M☉, respectively, though slightly higher

masses have been quoted in recent years, such as 1.14 M☉ and

0.92 M☉, or totalling 2.06 M☉. Alpha

Centauri A and B have absolute magnitudes of +4.38 and +5.71, respectively.

Stellar evolution theory implies both stars are slightly older than the Sun at

5 to 6 billion years, as derived by both mass and their spectral

characteristics.

Viewed from Earth, the apparent orbit of this binary star

means that its separation and position angle (PA) are in continuous change

throughout its projected orbit. Observed stellar positions in 2010 are

separated by 6.74 arcsecthrough the PA of 245.7°, reducing to 6.04 arcsec

through 251.8° in 2011. The closest recent approach was in February 2016, at

4.0 arcsec through 300°. The observed maximum separation of these stars is

about 22 arcsec, while the minimum distance is 1.7 arcsec. The widest

separation occurred during February 1976 and the next will be in January 2056.

In the true orbit, closest approach or periastron was in

August 1955, and next in May 2035. Furthest orbital separation at apastron last

occurred in May 1995 and the next will be in 2075. The apparent distance

between the two stars is rapidly decreasing, at least until 2019.

Proxima Centauri

The much fainter red dwarf Proxima Centauri, or simply Proxima,

is about 13,000 astronomical units (AU) away from Alpha Centauri AB. This is

equivalent to 0.21 ly or 1.9 trillion km—about 5% the distance between Alpha

Centauri AB and the Sun. Due to the large distance between Proxima and Alpha,

it was long unknown whether they were gravitationally bound. The true orbital

speed is necessarily small, and it was necessary to measure the speeds of

Proxima and Alpha with a great precision. Otherwise it was impossible to

ascertain whether Proxima is bound to Alpha or whether it is a completely

unrelated star that happens to be undergoing a close approach at a low relative

speed. Probability suggested that such low speed approaches would be rare and

unlikely, but it could not be ruled out.

It was only in 2017 that a paper by Kervella, et al., showed

that, based on high precision radial velocity measurements and with a high

degree of confidence, Proxima and Alpha Centauri are in fact gravitationally

bound. The orbital period of Proxima is approximately 550,000 years, with an

eccentricity of 0.50+0.08

Relative positions of Sun, Alpha Centauri AB and Proxima

Centauri. Grey dot is projection of Proxima Centauri, located at the same

distance as Alpha Centauri AB.

Proxima is a red dwarf of spectral class M6 Ve with an

absolute magnitude of +15.60, which is only a small fraction of the Sun's

luminosity. By mass, Proxima is calculated as 0.123±0.06 M☉ (rounded to 0.12 M☉) or about

one-eighth that of the Sun.

Kinematics

All components of

Alpha Centauri display significant proper motions against the background sky,

similar to the first-magnitude stars Sirius and Arcturus. Over the centuries,

this causes the apparent stellar positions to slowly change. Such motions

define the high-proper-motion stars. These stellar motions were unknown to

ancient astronomers. Most assumed that all stars were immortal and permanently

fixed on the celestial sphere, as stated in the works of the philosopher

Aristotle.

Edmond Halley in 1718 found that some stars had

significantly moved from their ancient astrometric positions. For example, the

bright star Arcturus (α Boo) in the constellation of Boötes showed an almost

0.5° difference in 1800 years, as did the brightest star, Sirius, in Canis

Major (α CMa). Halley's positional comparison was Ptolemy's catalogue of stars

contained in the Almagest whose original data included portions from an earlier

catalogue by Hipparchos during the 1st century BCE. Halley's proper motions

were mostly for northern stars, so the southern star Alpha Centauri was not

determined until the early 19th century.

Scottish-born observer Thomas Henderson in the 1830s at the

Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope discovered the true distance to

Alpha Centauri. He soon realized this system was likely to have a high proper

motion, In this case, the apparent stellar motion was found using Nicolas Louis

de Lacaille's astrometric observations of 1751–1752, by the observed

differences between the two measured positions in different epochs.

Distances of the nearest stars from 20,000 years ago until

80,000 years in the future

Combining the 2007 revised data from the Hipparcos Star

Catalogue (HIP) for the main binary star components, the average cumulative

common proper motion (cpm.) of Alpha Centauri AB is about 6.1 arcmin each

century, and 61.4 arcmin or 1.02° each millennium. These motions are about

one-fifth and twice, respectively, the diameter of the full Moon. Using

spectroscopy the mean radial velocity has been determined to be around 20 km/s

towards the Solar System.

Since α Centauri A and B are almost exactly in the plane of

the Milky Way as viewed from here, there are many stars behind them. In early

May, 2028, α Centauri A will pass between us and a distant red star. There is a

45% probability that an Einstein ring may be observed. Other near conjunctions

will also happen in the coming decades. These will allow very accurate

measurements of the proper motions of the components and may give information

on planets.

Predicted Future Changes

As the stars of Alpha Centauri approach the Solar System,

measured common proper motions and trigonometric parallaxes slowly increase.

These smaller effects will change until the star system becomes closest to

Earth, and begin reversing as the distance increases again. Furthermore, other

small changes also occur with the binary star's orbital elements. For example,

in the size of the semi-major axis of the orbital ellipse will increasing by

0.03 arcsec per century.. Also the observed position angles of the stars are

also subject to small cumulative changes (additional to position angle changes

caused by the Precession of the Equinoxes), as first determined by W. H. van

den Bos in 1926.

Based on knowing these common proper motions and radial

velocities, Alpha Centauri will continue to gradually brighten, passing just

north of the Southern Cross or Crux, before moving northwest and up towards the

celestial equator and away from the galactic plane. By about 29,700 AD, in the

present-day constellation of Hydra, Alpha Centauri will be 1.00 pc or 3.3 ly

away., though later calculations suggest 0.90 pc or 2.9 ly in 29,000 AD. Then

it will reach the stationary radial velocity (RVel) of 0.0 km/s and the maximum

apparent magnitude of −0.86v (which is comparable to present-day magnitude of

Canopus). Even during the time of this nearest approach, however, the apparent

magnitude of Alpha Centauri will still not surpass that of Sirius, which will

brighten incrementally over the next 60,000 years, and will continue to be the

brightest star as seen from Earth for the next 210,000 years.

About 28,000 years from now, the Alpha Centauri system will

then begin to move away from the Solar System, showing a positive radial

velocity. Because of visual perspective, these stars will reach a final

vanishing point and slowly disappear among the countless stars of the Milky

Way. Here this once bright yellow star will fall below naked-eye visibility.

somewhere in the faint present day southern constellation of

Telescopium.[citation needed] This unusual location results from the fact that

Alpha Centauri's orbit around the galactic centre is highly tilted with respect

to the plane of the Milky Way.

Viewed from the Earth in about 6200 AD, the common proper

motion of the main binary star Alpha Centaui AB will appear only 23 arcmin

north (or two-thirds the diameter of the Moon) of Beta Centauri and form a

spectacularly brilliant optical double star. Beta Centauri is in reality far

more distant than Alpha Centauri.

Planets

Proxima Centauri b

In August 2016, the European Southern Observatory announced

the discovery of a planet slightly larger than the Earth orbiting Proxima

Centauri. Proxima Centauri b was found using the radial velocity method, where

periodic Doppler shifts of spectral lines of the host star suggest an orbiting

object. From these readings, the radial velocity of the parent star relative to

the Earth is varying with an amplitude of about 2 metres (6.6 ft) per second.

The planet lies in the habitable zone of Proxima Centauri, but it is possible

that the planet is tidally locked to the star, resulting in temperature

extremes that would be difficult for life to overcome.

Alpha Centauri Bb & Bc

In 2012, a planet around Alpha Centauri B was announced, but

in 2015 a new analysis concluded that it almost certainly does not exist and

was just a spurious artefact of the data analysis.

Alpha Centauri Bc was first announced in 2013 by Demory et

al. It has an estimated orbital period of approximately 12 Earth days – smaller

than that of Mercury – with a semimajor axis of 0.10 AU and an eccentricity

smaller than 0.24.

Possible detection of another planet

On 25 March 2015, a scientific paper by Demory and

colleagues published transit results for Alpha Centauri B using the Hubble

Space Telescope for a total of 40 hours. They evidenced a transit event

possibly corresponding to a planetary body with a radius around 0.92 R⊕. This planet would most likely orbit Alpha Centauri B with an orbital

period of 20.4 days or less, with only a 5 percent chance of it having a longer

orbit. The median average of the likely orbits is 12.4 days with an impact

parameter of around 0–0.3. Its orbit would likely have an eccentricity

of 0.24 or less. Like the probably spurious Alpha Centauri Bb, it likely has

lakes of molten lava and would be far too close to Alpha Centauri B to harbour

life.

Possibility of additional planets

The discovery of planets orbiting other star systems,

including similar binary systems (Gamma Cephei), raises the possibility that

additional planets may exist in the Alpha Centauri system. Such planets could

orbit Alpha Centauri A or Alpha Centauri B individually, or be on large orbits

around the binary Alpha Centauri AB. Because both the principal stars are

fairly similar to the Sun (for example, in age and metallicity), astronomers

have been especially interested in making detailed searches for planets in the

Alpha Centauri system. Several established planet-hunting teams have used

various radial velocity or star transit methods in their searches around these

two bright stars. All the observational studies have so far failed to find any

evidence for brown dwarfs or gas giants.

In 2009, computer simulations showed that a planet might

have been able to form near the inner edge of Alpha Centauri B's habitable

zone, which extends from 0.5 to 0.9 AU from the star. Certain special assumptions,

such as considering that Alpha Centauri A and B may have initially formed with

a wider separation and later moved closer to each other (as might be possible

if they formed in a dense star cluster) would permit an accretion-friendly

environment farther from the star. Bodies around A would be able to orbit at

slightly farther distances due to A's stronger gravity. In addition, the lack

of any brown dwarfs or gas giants in close orbits around A or B make the

likelihood of terrestrial planets greater than otherwise. Theoretical studies

on the detectability via radial velocity analysis have shown that a dedicated

campaign of high-cadence observations with a 1-meter class telescope can

reliably detect a hypothetical planet of 1.8 M⊕ in the

habitable zone of B within three years.

Radial velocity measurements of Alpha Centauri B with High

Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher spectrograph ruled out planets of more

than 4 M⊕ to the distance of the habitable zone of

the star (orbital period P = 200 days).

Current estimates place the probability of finding an

earth-like planet around Alpha Centauri A or B at roughly 85%, although this

number remains uncertain. The observational thresholds for planet detection in

the habitable zones via the radial velocity method are currently (2017)

estimated to be about 50 M⊕ for Alpha

Centauri A, 8 M⊕ for B, and

0.5 M⊕for Proxima.

Theoretical planets

Early computer-generated models of planetary formation

predicted the existence of terrestrial planets around both Alpha Centauri A and

B, but most recent numerical investigations have shown that the gravitational

pull of the companion star renders the accretion of planets very difficult.

Despite these difficulties, given the similarities to the Sun in spectral

types, star type, age and probable stability of the orbits, it has been

suggested that this stellar system could hold one of the best possibilities for

harbouring extraterrestrial life on a potential planet.

In the Solar System both Jupiter and Saturn were probably

crucial in perturbing comets into the inner Solar System. Here, the comets

provided the inner planets with their own source of water and various other

ices. In the Alpha Centauri system, Proxima Centauri may have influenced the

planetary disk as the Alpha Centauri system was forming, enriching the area

around Alpha Centauri A and B with volatile materials. This would be discounted

if, for example, Alpha Centauri B happened to have gas giants orbiting Alpha

Centauri A (or conversely, Alpha Centauri A for Alpha Centauri B), or if the

stars B and A themselves were able to perturb comets into each other's inner

system as Jupiter and Saturn presumably have done in the Solar System. Such icy

bodies probably also reside in Oort clouds of other planetary systems, when

they are influenced gravitationally by either the gas giants or disruptions by

passing nearby stars many of these icy bodies then travel starwards. Such ideas

also apply to the close approach of Alpha Centauri or other stars to the Solar

System, where in the distant future of our Oort Cloud maybe disrupted enough to

see increased numbers of active comets. There is no direct evidence yet of the

existence of such an similar Oort cloud around Alpha Centauri AB, and

theoretically this may have been totally destroyed during the system's

formation.[citation needed]

To be in the star's habitable zone, any suspected planet

around Alpha Centauri A would have to be optimally placed about 1.25 AU away

[citation needed] – about halfway between the distances of Earth's orbit and

Mars's orbit in the Solar System – so as to have similar planetary temperatures

and conditions for liquid water to exist. For the slightly less luminous and

cooler Alpha Centauri B, the habitable zone would lie closer at about 0.7 AU

(100 million km), approximately the distance that Venus is from the Sun.

With the goal of finding evidence of such planets, both

Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri AB were among the listed "Tier 1"

target stars for NASA's Space Interferometry Mission(SIM). Detecting planets as

small as three Earth-masses or smaller within two astronomical units of a

"Tier 1" target would have been possible with this new instrument.

The SIM mission, however, was cancelled due to financial issues in 2010.

Circumstellar discs

Based on observations between 2007 and 2012, a study found a

slight excess of emissions in the 24 µm (mid/far-infrared) band surrounding α

Centauri AB, which may be interpreted as evidence for a sparse circumstellar

disc or dense interplanetary dust. The total mass was estimated to be between

10−7 to 10−6 the mass of the Moon, or 10-100 times the mass of the Solar

System's zodiacal cloud. If such a disc existed around both stars, α Centauri

A's disc would likely be stable to 2.8 AU, and α Centauri B's would likely be

stable to 2.5 AU. This would put A's disc entirely within the frost line, and a

small part of B's outer disc just outside.

View from this system

Viewed from near the Alpha Centauri system, the sky would

appear very much as it does for an observer on Earth, except that Centaurus

would be missing its brightest star. The Sun would be a yellow star of an

apparent visual magnitude of +0.5 in eastern Cassiopeia, at the antipodal point

of Alpha Centauri's current right ascension and declination, at 02h 39m 35s

+60° 50′ (2000). This place is close to the 3.4-magnitude star ε Cassiopeiae.

Because of the placement of the Sun, an interstellar or alien observer would

find the \/\/ of Cassiopeia had become a /\/\/ shape[note 1]nearly in front of

the Heart Nebula in Cassiopeia. Sirius lies less than a degree from Betelgeuse

in the otherwise unmodified Orion and with a magnitude of −1.2 is a little

fainter than from Earth but still the brightest star in the Alpha Centauri sky.

Procyon is also displaced into the middle of Gemini, outshining Pollux, whereas

both Vega and Altair are shifted northwestward relative to Deneb (which barely

moves, due to its great distance), giving the Summer Triangle a more

equilateral appearance.

From Proxima Centauri b

From Proxima Centauri b, Alpha Centauri AB would appear like

two close bright stars with the combined apparent magnitude of −6.8. Depending

on the binary's orbital position, the bright stars would appear noticeably divisible

to the naked eye, or occasionally, but briefly, as a single unresolved star.

Based on the calculated absolute magnitudes, the visual apparent magnitudes of

Alpha Centauri A and B would be −6.5 and −5.2, respectively.

From a hypothetical A or B planet

An observer on a hypothetical planet orbiting around either

Alpha Centauri A or Alpha Centauri B would see the other star of the binary

system as an intensely bright object in the night sky, showing a small but

discernible disk while near periapse: A up to 210 arc seconds, B up to 155 arc

seconds. Near apoapse, the disc would shrink to 60 arc seconds for A, 43 arc

seconds for B, being too small to resolve by naked eye. In any case, the

dazzling surface brightness could make the discs harder to resolve than a

similarly sized less bright object.

For example, some theoretical planet orbiting about 1.25 AU

from Alpha Centauri A (so that the star appears roughly as bright as the Sun

viewed from the Earth) would see Alpha Centauri B orbit the entire sky once

roughly every one year and three months (or 1.3(4) a), the planet's own orbital

period. Added to this would be the changing apparent position of Alpha Centauri

B during its long eighty-year elliptical orbit with respect to Alpha Centauri

A. (The average speed, at 4.5 degrees per Earth year, is comparable in speed to

Uranus here. With the eccentricity of the orbit, the maximum speed near

periapse, about 18 degrees per Earth year, is faster than Saturn, but slower

than Jupiter. The minimum speed near apoapse, about 1.8 degrees per Earth year,

is slower than Neptune.) Depending on its and the planet's position on their

respective orbits, Alpha Centauri B would vary in apparent magnitude between

−18.2 (dimmest) and −21.0 (brightest). These visual apparent magnitudes are

much dimmer than the apparent magnitude of the Sun as viewed from the Earth

(−26.7). The difference of 5.7 to 8.6 magnitudes means Alpha Centauri B would

appear, on a linear scale, 2500 to 190 times dimmer than Alpha Centauri A (or

the Sun viewed from the Earth), but also 190 to 2500 times brighter than the

full Moon as seen from the Earth (−12.5).

Also, if another similar planet orbited at 0.71 AU from

Alpha Centauri B (so that in turn Alpha Centauri B appeared as bright as the

Sun seen from the Earth), this hypothetical planet would receive slightly more

light from the more luminous Alpha Centauri A, which would shine 4.7 to 7.3

magnitudes dimmer than Alpha Centauri B (or the Sun seen from the Earth),

ranging in apparent magnitude between −19.4 (dimmest) and −22.1 (brightest).

Thus Alpha Centauri A would appear between 830 and 70 times dimmer than the Sun

but some 580 to 6900 times brighter than the full Moon. During the orbital

period of such a planet of 0.6(3) a, an observer on the planet would see this

intensely bright companion star circle the sky just as humans see with the

Solar System's planets. Furthermore, Alpha Centauri A's sidereal period of

approximately eighty years means that this star would move through the local

ecliptic as slowly as Uranus with its eighty-four year period, but as the orbit

of Alpha Centauri A is more elliptical, its apparent magnitude will be far more

variable. Although intensely bright to the eye, the overall illumination would

not significantly affect climate nor influence normal plant photosynthesis.

An observer on the hypothetical planet would notice a change

in orientation to very-long-baseline interferometry reference points

commensurate with the binary orbit periodicity plus or minus any local effects

such as precession or nutation.

Assuming this hypothetical planet had a low orbital

inclination with respect to the mutual orbit of Alpha Centauri A and B, then

the secondary star would start beside the primary at "stellar"

conjunction. Half the period later, at "stellar" opposition, both

stars would be opposite each other in the sky. As a net result, both the local

sun and the other star would each be in the sky for half a day, like Sun and

Moon are both above the horizon for half a day. But during stellar conjunction,

the other star being "new" would be in the sky during daytime, while

during the opposition, the other star being "full" would be in the

sky for the whole night. In an Earth-like atmosphere, the light of the other

star would be appreciably scattered, causing the sky to be perceptibly blue

though darker than during daytime, like during twilight or total solar eclipse.

Humans could easily walk around and clearly see the surrounding terrain, and

reading a book would be quite possible without any artificial light. Over the

following half period, the secondary star would be in the sky for a

progressively decreasing part of the night (and an increasing part of the day)

until at the next conjunction the secondary star would only be in the sky

during daytime near the primary star.

From a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri A or B, Proxima

Centauri would appear as a fourth to fifth magnitude star, as bright as the

faint stars of the constellation of Ursa Minor.

Other names

In modern literature, Rigil Kent (also Rigel Kent and

variants;[note 2] /ˈraɪdʒəl ˈkɛnt/) and Toliman, were cited as colloquial

alternative names of Alpha Centauri.

Rigil Kent is short for Rigil Kentaurus, which is sometimes

further abbreviated to Rigil or Rigel, though that is ambiguous with Beta

Orionis, which is also called Rigel. Although the short form Rigel Kent is

often cited as an alternative name, the star system is most widely referred to

by its Bayer designation Alpha Centauri.

The name Toliman originates with Jacobus Golius' edition of

Al-Farghani's Compendium (published posthumously in 1669). Tolimân is Golius'

latinization of the Arabic name الظلمانal-Ẓulmān

"the ostriches", the name of an asterism of which Alpha Centauri

formed the main star.

During the 19th century, the northern amateur popularist

Elijah H. Burritt used the now-obscure name Bungula, possibly coined from

"β" and the Latin ungula ("hoof").

Together, Alpha and Beta Centauri form the "Southern

Pointers" or "The Pointers", as they point towards the Southern

Cross, the asterism of the constellation of Crux.

In Standard Mandarin Chinese, 南門 Nán Mén, meaning Southern Gate,

refers to an asterism consisting of α Centauri and ε Centauri. Consequently, α

Centauri itself is known as 南門二 Nán Mén Èr, the Second Star of the Southern Gate.

To the Australian aboriginal Boorong people of northwestern

Victoria, Alpha and Beta Centauri are Bermbermgle, two brothers noted for their

courage and destructiveness, who speared and killed Tchingal "The

Emu" (the Coalsack Nebula). The form in Wotjobaluk is Bram-bram-bult.

Exploration

Alpha Centauri is envisioned as a likely first target for

manned or unmanned interstellar exploration. Crossing the huge distance between

the Sun and Alpha Centauri using current spacecraft technologies would take

several millennia, though the possibility of nuclear pulse propulsionor laser

light sail technology, as considered in the Breakthrough Starshot program,

could reduce the journey time to a matter of decades.

Breakthrough Starshot is a proof-of-concept initiative to

send a fleet of ultra-fast light-driven nanocraft to explore the Alpha Centauri

system, which could pave the way for a first launch within the next generation.

An objective of the mission would be to make a fly-by of, and possibly

photograph, any planets that might exist in the system. Proxima Centauri b,

announced by the European Southern Observatory(ESO) in August 2016, would be a

target for the Starshot program.

In January 2017, Breakthrough Initiatives and the ESO

entered a collaboration to enable and implement a search for habitable planets

in the Alpha Centauri system. The agreement involves Breakthrough Initiatives

providing funding for an upgrade to the VISIR (VLT Imager and Spectrometer for

mid-Infrared) instrument on ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. This

upgrade will greatly increase the likelihood of planet detection in the system.

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis

took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the

dimensions of the universe. To support his claim of the Great Andromeda Nebula

being, in fact, an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark

lanes within Andromeda which resembled the dust clouds in our own galaxy, as

well as historical observations of Andromeda Galaxy's significant Doppler

shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented a method to estimate the distance of

Andromeda using the measured velocities of its stars. His result placed the

Andromeda Nebula far outside our galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsecs

(1,500,000 ly). Edwin Hubble settled the debate in 1925 when he identified

extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos

of Andromeda. These were made using the 2.5-metre (100-in) Hooker telescope,

and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His

measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature is not a cluster of

stars and gas within our own Galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a

significant distance from the Milky Way.

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis

took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the

dimensions of the universe. To support his claim of the Great Andromeda Nebula

being, in fact, an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark

lanes within Andromeda which resembled the dust clouds in our own galaxy, as

well as historical observations of Andromeda Galaxy's significant Doppler

shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented a method to estimate the distance of

Andromeda using the measured velocities of its stars. His result placed the

Andromeda Nebula far outside our galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsecs

(1,500,000 ly). Edwin Hubble settled the debate in 1925 when he identified

extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos

of Andromeda. These were made using the 2.5-metre (100-in) Hooker telescope,

and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His

measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature is not a cluster of

stars and gas within our own Galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a

significant distance from the Milky Way.