Dwarf Planets

(Dwarf Planets: history,Exploration,mass moons,Name of dwarf Planets)

A

dwarf planet is a planetary-mass object that is neither a planet nor a

natural satellite. That is, it is in direct orbit of a star, and is

massive enough for its gravity to crush it into a hydrostatically

equilibrious shape (usually a spheroid), but has not cleared the neighborhood of other material around its orbit.

The

term dwarf planet was adopted in 2006 as part of a three-way

categorization of bodies orbiting the Sun, brought about by an increase

in discoveries of objects farther away from the Sun than Neptune that

rivaled Pluto in size, and finally precipitated by the discovery of an

even more massive object, Eris. The exclusion of dwarf planets from the

roster of planets by the IAU has been both praised and criticized; it

was said to be the "right decision" by astronomer Mike Brown, who

discovered Eris and other new dwarf planets, but has been rejected by

Alan Stern, who had coined the term dwarf planet in April 1991.

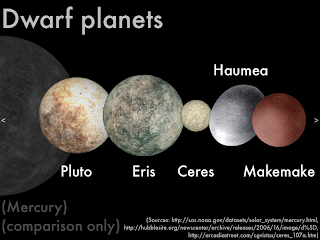

The

International Astronomical Union (IAU) currently recognizes five dwarf

planets: Ceres; Pluto; Haumea; Makemake; and Eris. Brown criticizes this

official recognition: "A reasonable person might think that this means

that there are five known objects in the solar system which fit the IAU

definition of dwarf planet, but this reasonable person would be nowhere

close to correct."

Another

hundred or so known objects in the Solar System are suspected to be

dwarf planets. Estimates are that up to 200 dwarf planets will be

identified when the entire region known as the Kuiper belt is explored,

and that the number may exceed 10,000 when objects scattered outside the

Kuiper belt are considered.[dead link] Individual astronomers recognize

several of these, and in August 2011 Mike Brown published a list of 390

candidate objects, ranging from "nearly certain" to "possible" dwarf

planets. Brown currently identifies ten known trans-Neptunian

objects—the four accepted by the IAU plus 2007 OR10, Quaoar, Sedna,

Orcus, (307261) 2002 MS4 and Salacia—as "virtually certain", with

another twenty highly likely. Stern states that there are more than a

dozen known dwarf planets.

Only

two of these bodies, Ceres and Pluto, have been observed in enough

detail to demonstrate that they actually fit the IAU's definition. The

IAU accepted Eris as a dwarf planet because it is more massive than

Pluto. They subsequently decided that unnamed trans-Neptunian objects

with an absolute magnitude brighter than +1 (and hence a diameter of

≥838 km assuming a geometric albedo of ≤1) are to be named under the

assumption that they are dwarf planets.

The classification of bodies in other planetary systems with the characteristics of dwarf planets has not been addressed.

History of the concept

Starting

in 1801, astronomers discovered Ceres and other bodies between Mars and

Jupiter which were for decades considered to be planets. Between then

and around 1851, when the number of planets had reached 23, astronomers

started using the word asteroid for the smaller bodies and then stopped

naming or classifying them as planets.

With the discovery of Pluto in 1930, most astronomers considered the Solar System to have

nine planets, along with thousands of significantly smaller bodies

(asteroids and comets). For almost 50 years Pluto was thought to be

larger than Mercury, but with the discovery in 1978 of Pluto's moon

Charon, it became possible to measure Pluto's mass accurately and to

determine that it was much smaller than initial estimates. It was

roughly one-twentieth the mass of Mercury, which made Pluto by far the

smallest planet. Although it was still more than ten times as massive as

the largest object in the asteroid belt, Ceres, it had one-fifth the

mass of Earth's Moon. Furthermore, having some unusual characteristics,

such as large orbital eccentricity and a high orbital inclination, it

became evident that it was a different kind of body from any of the

other planets.

In

the 1990s, astronomers began to find objects in the same region of

space as Pluto (now known as the Kuiper belt), and some even farther

away. Many of these shared several of Pluto's key orbital

characteristics, and Pluto started being seen as the largest member of a

new class of objects, plutinos. This led some astronomers to stop

referring to Pluto as a planet. Several terms, including subplanet and

planetoid, started to be used for the bodies now known as dwarf planets.

By 2005, three trans-Neptunian objects comparable in size to Pluto

(Quaoar, Sedna, and Eris) had been reported. It became clear that either

they would also have to be classified as planets, or Pluto would have

to be reclassified. Astronomers were also confident that more objects as

large as Pluto would be discovered, and the number of planets would

start growing quickly if Pluto were to remain a planet.

Eris

(then known as 2003 UB313) was discovered in January 2005; it was

thought to be slightly larger than Pluto, and some reports informally

referred to it as the tenth planet. As a consequence, the issue became a

matter of intense debate during the IAU General Assembly in August

2006. The IAU's initial draft proposal included Charon, Eris, and Ceres

in the list of planets. After many astronomers objected to this

proposal, an alternative was drawn up by Uruguayan astronomer Julio

Ángel Fernández: he proposed an intermediate category for objects large

enough to be round but which had not cleared their orbits of

planetesimals. Dropping Charon from the list, the new proposal also

removed Pluto, Ceres, and Eris, because they have not cleared their

orbits.

The IAU's final Resolution 5A preserved this three-category system for the celestial bodies orbiting the Sun. It reads:

The

IAU ... resolves that planets and other bodies, except satellites, in

our Solar System be defined into three distinct categories in the

following way:

(1)

A planet1 is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b)

has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces

so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and

(c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

(2)

A "dwarf planet" is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the

Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body

forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round)

shape,2 (c) has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit, and (d)

is not a satellite.

(3) All other objects,3 except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as "Small Solar System Bodies."

Recognized

The

IAU has recognized five bodies as dwarf planets since 2008: Ceres,

Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. Ceres and Pluto are known to be dwarf

planets through direct observation. Eris is recognized as a dwarf

planet because it is more massive than Pluto (measurements by New

Horizons indicate that Pluto's diameter is larger than that of Eris),

whereas Haumea and Makemake qualify based on their absolute magnitudes.

In relative distance from the Sun, the five are:

1. Ceres –

discovered on January 1, 1801, 45 years before Neptune. Considered a

planet for half a century before reclassification as an asteroid.

Accepted as a dwarf planet by the IAU on September 13, 2006.

2. Pluto ♇ – discovered on February 18, 1930. Classified as a planet for 76 years. Reclassified as a dwarf planet by the IAU on August 24, 2006.

3. Haumea – discovered on December 28, 2004. Accepted by the IAU as a dwarf planet on September 17, 2008.

4. Makemake – discovered on March 31, 2005. Accepted by the IAU as a dwarf planet on July 11, 2008.

5. Eris

– discovered on January 5, 2005. Called the "tenth planet" in media

reports. Accepted by the IAU as a dwarf planet on September 13, 2006.

Exploration

On

March 6, 2015, the Dawn spacecraft began to orbit Ceres, becoming the

first spacecraft to orbit a dwarf planet. On July 14, 2015, the New

Horizons space probe flew by Pluto and its five moons. Dawn has also

explored the former dwarf planet Vesta. Phoebe has been explored by

Cassini (most recently) and Voyager 2, which also explored Triton. These

three are thought to be former dwarf planets and therefore their

exploration helps in the study of the evolution of dwarf planets.

Planetary-mass moons

Nineteen

moons are known to be massive enough to have relaxed into a rounded

shape under their own gravity, and seven of them are more massive than

either Eris or Pluto. They are not physically distinct from the dwarf

planets, but are not dwarf planets because they do not directly orbit

the Sun. The seven that are more massive than Eris are the Moon, the

four Galilean moons of Jupiter (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto), one

moon of Saturn (Titan), and one moon of Neptune (Triton). The others

are six moons of Saturn (Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and

Iapetus), five moons of Uranus (Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and

Oberon), and one moon of Pluto (Charon). There are additional

possibilities among TNOs, including Dysnomia orbiting Eris. Alan Stern

calls these moons "satellite planets", one of three categories of planet

together with dwarf planets and classical planets. The term planemo

("planetary-mass object") covers all three.

In

a draft resolution for the IAU definition of planet, both Pluto and

Charon would have been considered dwarf planets in a binary system,

given that they both satisfied the mass and shape requirements for dwarf

planets and revolved around a common center of mass located between the

two bodies (rather than within one of the bodies).[note 1] The IAU

currently states that Charon is not considered to be a dwarf planet and

is just a satellite of Pluto, although the idea that Charon might

qualify to be a dwarf planet in its own right may be considered at a

later date. The location of the barycenter depends not only on the

relative masses of the bodies, but also on the distance between them;

the barycenter of the Sun–Jupiter orbit, for example, lies outside the

Sun.

Dwarf planets and possible dwarf planets

Many trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) are thought to have icy cores and therefore would

require a diameter of perhaps 400 km (250 mi)—only about 3% of that of

Earth—to relax into gravitational equilibrium. As of January 2015, about

150 known TNOs are considered potential dwarf planets, although only

rough estimates of the diameters of most of these objects are available.

A team is investigating thirty of these, and think that the number will

eventually prove to be around 200 in the Kuiper belt, with thousands

more beyond.

Many trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) are thought to have icy cores and therefore would

require a diameter of perhaps 400 km (250 mi)—only about 3% of that of

Earth—to relax into gravitational equilibrium. As of January 2015, about

150 known TNOs are considered potential dwarf planets, although only

rough estimates of the diameters of most of these objects are available.

A team is investigating thirty of these, and think that the number will

eventually prove to be around 200 in the Kuiper belt, with thousands

more beyond.

0 comments:

Post a Comment